|

Mark Kostabi on

Chris Hammerlein

Chris Hammerlein draws so freely, so stream-of-conscious, and for so long that he just can't remember his own images. He draws something like twenty each day, sometimes sitting at his desk for eight hours at a time. And then they just slip from memory.

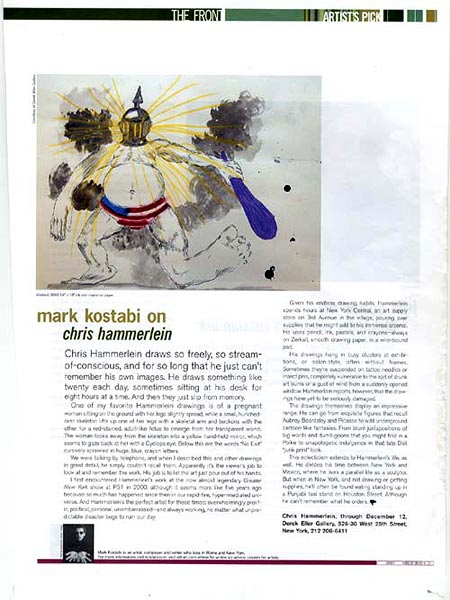

One of my favorite Hammerlein drawings is of a pregnant woman sitting on the ground with her legs slightly spread, while a small, hunched-over skeleton lifts up one of her legs with a skeletal arm and beckons with the other for a red-stained, adult-like fetus to emerge from her transparent womb. The Woman looks away from the skeleton into a yellow hand-held mirror, which seems to gaze back at her with a Cyclops eye. Below this are the words "No Exit" cursively scrawled in huge blue, crayon letters.

We were talking by telephone, and when I described this and other drawings in great detail, he simply couldn't recall them. Apparently it's the viewer's job to look at and remember the work. His job is to let the art just pour out of his hands.

I first encountered Hammerlein's work at the now almost legendary Greater New York show at PS1 in 2000, although it seems more like five years ago because so much has happened since then in our rapid-fire, hyper-mediated universe. And Hammerlien's the perfect artist or these times: overwhelmingly prolific, political, personal, unembarrassed- and always working, no matter what unpredictable disaster begs to ruin our day.

Given his endless drawing habits, Hammerlein spends hours at New York Central, an art supply store on 3rd Avenue in the village, pouring over supplies that he might add to his immense arsenal. He uses pencil, ink, pastels, and crayons- always on Zerkall, smooth drawing paper, in a wire-bound pad.

His drawings hang in busy clusters at exhibitions, or salon-style, often without frames. Sometimes they're suspended on tattoo needles or insect pins, completely vulnerable to the spit of drunk art bums or a gust of wind from a suddenly opened window. Hammerlein reports, however, that the drawings have yet to be seriously damaged.

The drawings themselves display an impressive range. He can go from exquisite figures that recall Aubrey Beardsley and Picasso to wild underground carton-like fantasies. From blunt juxtapositions of big words and dumb goons that you might find in a Polke to unapologetic indulgence in that late Dali "junk print" look.

This eclecticism extends to Hammmerlein's life, as well. He divides this time between New York and Mexico, where he lives a parallel life as a sculptor. But when in New York, and not drawing or getting supplies, he'll often be found eating standing up in a Punjabi taxi stand on Houston Street. Although he can't remember what he orders.

Chris Hammerlein, through December 12, Derek Eller Gallery, 526-30 West 25th Street, New York, 212-206-6411

December 2002 - January 2003